POLITICO Panel: Will Hybrid Work Fix or Fuel Gender Gaps?

The bad is that hybrid work can exacerbate gender gaps, but the good news is better policies can break down equity barriers and bring other business benefits

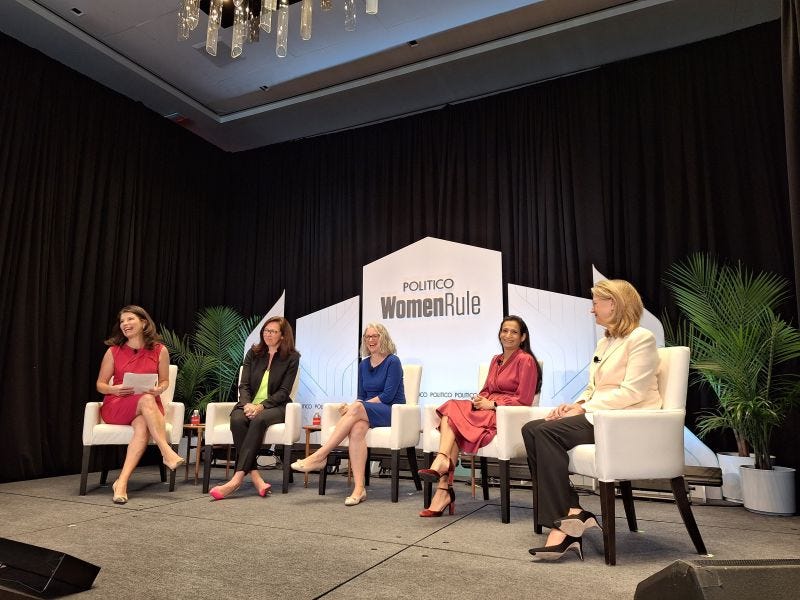

At the end of July I was invited by POLITICO to participate in a panel for their Women Rule: Elevating Women Leaders in the New Workplace event on the topic of hybrid work – will it fix or fuel gender gaps? You can watch the whole session here.

I was thrilled to be asked to be on this panel because this is a question that I’ve been obsessed with for a long time. Certainly since the pandemic made remote work more common and accessible than ever before. But even before COVID I wrestled with the pros and cons of flexibility as it relates to women’s workforce participation and leadership.

It’s a thorny issue because there is an interplay between the dynamics in the workplace and the dynamics at home. Women are more likely to seek out and ask for flexible work arrangements because they are often the parent or adult child who is taking on a disproportionate share of unpaid domestic care and other labor. At the very end of the panel I made the point that for too long men who had support at home, in the form of a stay-at-home-wife or even just a partner with more flexibility, were pushed up the ladder by virtue of having that extra support and the time it frees up to accomplish professional goals.

If we don’t do more to tackle gender inequality at home we’ll never close the remaining gender gaps in income, wealth and leadership.

But, the answer is not to eliminate flexibility. Lack of flexibility pushes women out of the labor force completely, and that absolutely exacerbates gender gaps and leads to worse financial outcomes for women.

(More importantly, leaders have to understand that the cat is out of the bag, so to speak, on the issue of flexibility. Workers, of all genders, expect some level of flex, which is why “return to office” mandates have been so ineffectual. Companies that try to impose rigid work policies will lose out on talent.)

What’s most important now is that leaders and managers be intentional. Not just with their return to office plans, but more broadly with how we think about work, productivity, collaboration and all that goes into knowledge work.

To best attract talent and continue to improve gender equality at all levels, leaders should be focused on supporting their employees with flexibility regardless of gender and then assessing employees based on output and value, not their ability or willingness to overwork. (I’m going to admit that last bit is hard – who doesn’t want workers who are willing to put in 110%? But the downsides of rewarding overwork far outweigh the upsides of extra productivity, much of which is marginal at best and too often actually a mirage.)

If we are being honest, we’ve been doing a bad job at all of this for a long time. We have, generally, treated knowledge work the way we always treated manual work – by assuming that number of hours worked (in a specific physical location, at specific times) was the best way to measure productivity and worker value. But knowledge work doesn’t work that way.

One size policies won’t fit all organizations or even all teams. These are the questions leaders need to ask as they begin to craft plans and policies for the new ways we work:

What problems does being in the office solve? What problems does remote work solve? Deciding whether and how to implement a return to office or hybrid work policy comes down to what challenges different ways of working create or solve. In-office work can, when done well, foster collaboration and better communication. But allowing for remote days alleviates pressure, especially for those with caregiving responsibilities. Finding the right balance – and thinking through the needs of collaboration and availability – isn’t going to be easy. But just imposing a top-down policy can backfire.

Who’s clamoring to be back in the office? Who’s clamoring for work from home? This isn’t to suggest a “rightness” or “wrongness” to one way or the other. But if you see patterns by generation, caregiving status, gender, race or geography it’s worth getting curious and asking questions. Are there people who are more comfortable being in the office because that’s how it’s “always been done”? Or maybe younger workers feel the need for more hands-on guidance. Those with long commutes may benefit from more flexibility in hours along with more remote days. And, these decisions need to be viewed through a lens of equity – are some groups advantaged or disadvantaged by current or proposed policies?

How are we evaluating performance, assessing potential, and assigning non-promotable tasks (a.k.a., “office housework”)? Judging employees by a “face time” metric was always inadequate. It always overprivileged those who put in long hours in a specific place, whether or not they were providing good value during that time. And it always underprivileged those who were more efficient. Getting more sophisticated with performance management will be the cheat code of the future.

Does your organization support middle managers with the training and resources to be effective managers? One reason we’ve always been so bad at performance management, and defaulted to hours, is because assessing value is hard work. It takes more time than just noticing that Jane comes in at 9 a.m. and leaves at 7 p.m. but John doesn’t log onto Slack until after 10 a.m. We need to give managers training now how to assess work and productivity and give them the time needed to do that. We also need to make sure teams are resourced to do the job they are being asked to do. A lot of toxicity in modern companies starts with wildly unrealistic expectations for workloads.

If well implemented, these ideas can make organization both more equitable and more successful, by making it easier for smart and talented people to do the work they need to do with less stress.

"for too long men who had support at home, in the form of a stay-at-home-wife or even just a partner with more flexibility, were pushed up the ladder by virtue of having that extra support and the time it frees up to accomplish professional goals. " This. And to your point, how can we support everyone's professional goals, especially those with less or little support at home?